Governor Bradford described

Squanto:

“Squanto stayed with them and was their interpreter and was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation.

… He showed them how to plant corn, where to take fish and other commodities, and guided them to unknown places, and never left them till he died.”

Governor Bradford added:

“The settlers, as many as were able, then began to plant their corn, in which service Squanto stood them in good stead, showing them how to plant it and cultivate it.

… He also told them that unless they got fish to manure this exhausted old soil, it would come to nothing,

and he showed them that in the middle of April plenty of fish would come up the brook by which they had begun to build, and taught them how to catch it, and where to get other necessary provisions; all of which they found true by experience …”

Though records are scarce, it appears that Squanto was kidnapped around 1605, along with other Patuxet natives, by George Weymouth’s expedition and taken to England where he lived with Sir Ferdinando Gorges of Plymouth.

On Sir Ferdinando’s 1614 expedition to map the New England coast, Squantoserved as interpreter.

Allowed to return to his tribe, Squanto, with other Patuxet and Nausets, was kidnapped again by Captain Thomas Hunt, who intended to sell them at the slave markets of Malaga, Spain, a city notorious for the slave trade which began during its Muslim occupation.

Governor Bradford wrote of Squanto:

“He was a native of these parts, and had been one of the few survivors of the plague hereabouts.

He was carried away with others by one Hunt, a captain of a ship, who intended to sell them for slaves in Spain …”

Squanto was rescued by some Christian friars, who introduced him to Christianity and gave him his freedom.

Squanto returned to England where he was hired by John Slaney, treasurer of the Newfoundland Company. Squanto worked for Newfoundland Colony governor John Mason, then for Captain Thomas Dermer, agent of Sir Ferdinando Gorges.

Governor William Bradford wrote of Squanto:

“He got away for England, and was received by a merchant in London, and employed in Newfoundland and other parts, and lastly brought into these parts by a Captain Dermer, a gentleman employed by Sir Ferdinand Gorges …”

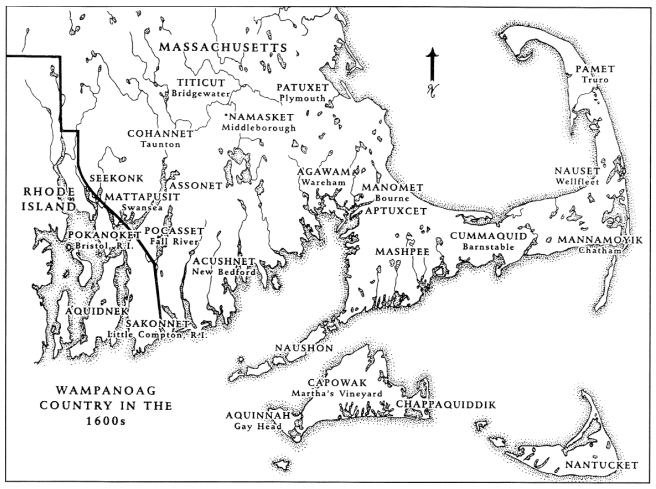

When Squanto finally returned to his tribe in 1619, he found that all of them had died of a plague. Depressed, he lived with the neighboring Wampanoag tribe.

As tragic as his kidnapping was, had Squanto not been kidnapped he most likely would have died in that plague.

Pilgrim Governor William Bradford continued:

“Captain Dermer had been here the same year that the people of the Mayflower arrived, as appears in an account written by him, and given to me by a friend, bearing date, June 30th, 1620 …

‘I will first begin,’ says he, ‘with the place from which Squanto (or Tisquantem) was taken away, which in Captain Smith’s map is called ‘Plymouth’; and I would that Plymouth (England) had the same commodities.

I could wish that the first plantation might be situated here, if there came to the number of fifty persons or upward; otherwise at Charlton, because there the savages are less to be feared …

The Pokanokets (Patuxet), who live to the west of Plymouth, bear an inveterate hatred to the English …

… For this reason Squanto cannot deny but they would have killed me when I was at Namasket, had he not interceded hard for me.'”

Get the book American Minute-Notable Events of American Significance Remembered on the Date They Occurred

The plague that wiped out the Patuxet may have come from survivors of a shipwreck at Cape Code three years before the Pilgrims landed.

Governor William Bradford described the fate of a French ship which wrecked in 1617:

“About three years before, a French ship was wrecked at Cape Cod, but the men got ashore and saved their lives and a large part of their provisions.

When the Indians heard of it, they surrounded them and never left watching and dogging them

till they got the advantage and killed them, all but three or four, whom they kept,

and sent from one Sachem to another, making sport with them and using them worse than slaves …”

Bradford added:

“Another Indian, called Hobbamok came to live with them, a fine strong man, of some account amongst the Indians for his valor and qualities.

He remained very faithful to the English till he died.

He and Squanto having gone upon business among the Indians, a Sachem called Corbitant…began to quarrel with them, and threatened to stab Hobbamok;

but he being a strong man, cleared himself of him, and came running away, all sweating, and told the Governor what had befallen him, and that he feared they had killed Squanto …

…So it was resolved to send the Captain and fourteen men, well armed… The Captain, giving orders to let none escape, entered to search for him.

But Corbitant had gone away that day; so they missed him, but learned that Squanto was alive, and that Corbitant had only threatened to kill him, and made as if to stab him, but did not …”

Bradford wrote further:

“After this, on the 18th of September, they sent out their shallop (small sailboat) with ten men and Squantoas guide and interpreter to the Massachusetts, to explore the bay and trade with the natives, which they accomplished, and were kindly received…

Nor was there a man among them who had ever seen a beaver skin till they came out, and were instructed by Squanto.”

Governor William Bradford wrote the account of Squanto’sdeath in LATE SEPTEMBER 1622:

“Captain Standish was appointed to go with them, and Squanto as a guide and interpreter, about the LATTER END OF SEPTEMBER;

but the winds drove them in; and putting out again, Captain Standish fell ill with fever, so the Governor (Bradford) went himself.

But they could not get round the shoals of Cape Cod, for flats and breakers, and Squanto could not direct them better.

The Captain of the boat dare not venture any further, so they put into Manamoick Bay, and got what they could there…”

Governor Bradford concluded:

“Here Squanto fell ill of Indian fever, bleeding much at the nose, which the Indians take for a symptom of death, and within a few days he died.

He begged the Governor to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen’s God in Heaven, and bequeathed several of his things to some of his English friends, as remembrances.

His death was a great loss.”